This post is (or will be) a rambling confluence of a few different stories. Back in June, I posted about a Brown Pelican I saw flying over Bolsa Chica at dusk. I photographed the bird in silhouette as it trailed a triple-hook fishing lure from its pouch.

I obviously have no way of knowing what will happen to the pelican I saw in that flyover, but in my Facebook feed today, I saw a post from International Bird Rescue, an amazing rescue and rehabilitation center in the Bay Area. Their photo is of a rescued pelican with the same type of fishing lure caught in the bird’s pouch … and they link out to a post about birds and fishing gear injuries. The photo of the pelican gave me hope, however slim, that the injured pelican I saw might someday find his or her good fortune in the hands of capable rescuers like the ones at Bird Rescue.

This ties into a post at 10,000 Birds by blogger, birder and conservationist Larry Jordan who put together a a gorgeous, illustrated piece about the very same International Bird Rescue — a great article that deserves a read.

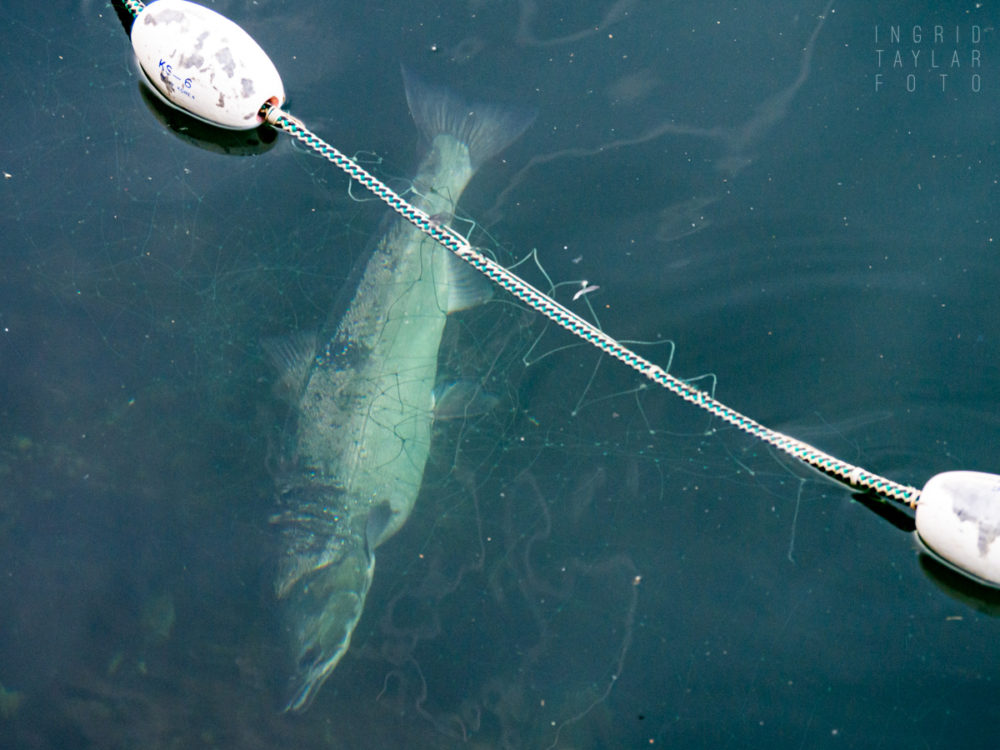

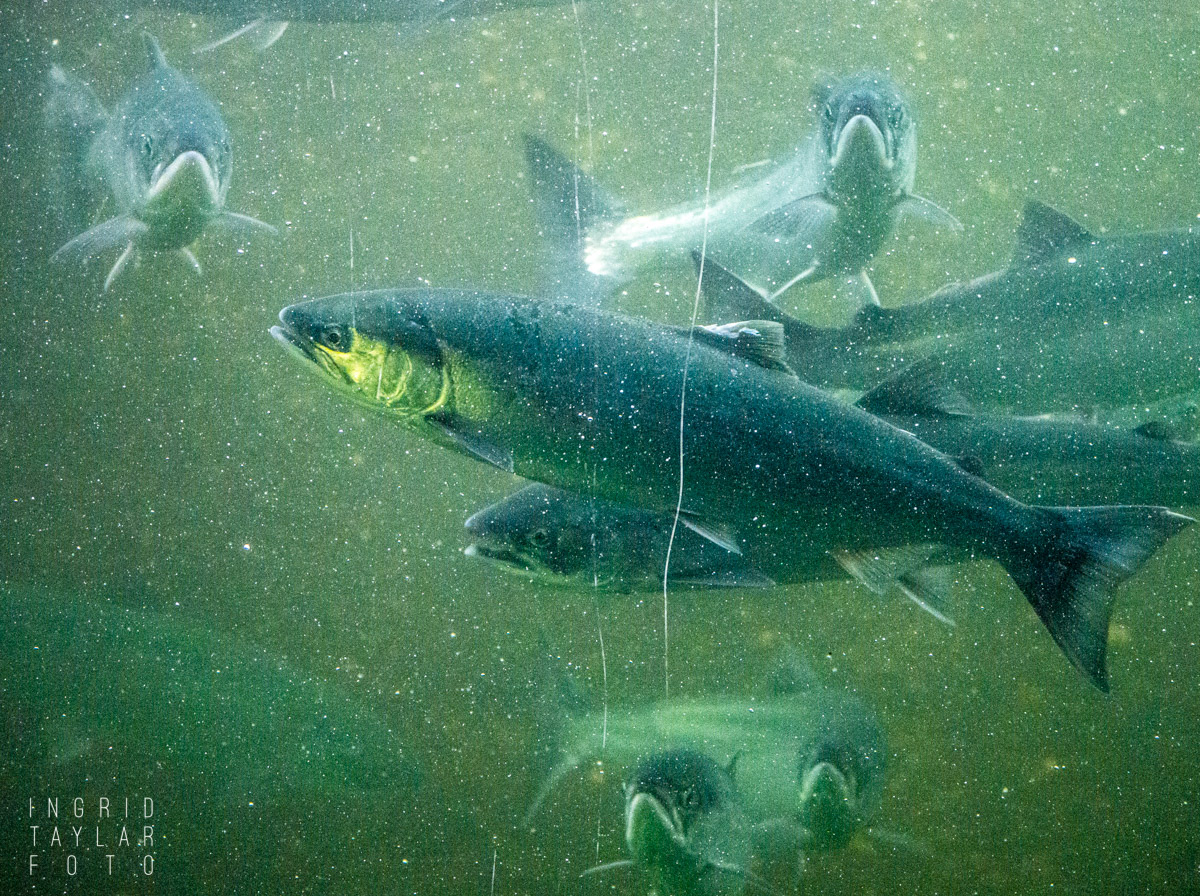

There’s a loose thread from this subject — fishing gear and wildlife — to a photo I posted on Flickr a few days ago. I shot an image of salmon caught in a gill net. I know … I’m on a real upbeat trajectory here.

If you’re interested in the context, you can read my Flickr caption here.

I felt awful walking away from that scene, particularly after checking out the fish ladder viewing area and seeing the normally busy 18th weir, almost devoid of salmon. The gillnets are strung across a big section of the channel which leads to the ladder, hence the reduced number of salmon travelers.

Seattle, Washington

Ruminating on gillnets and entanglements, my mind raced to the gulls we tried to rescue out in Westport, Washington — gulls entangled in lazy, torn netting over bait ponds.

Then that train of thought took me back to one particularly matted clump of fishing line and lure Hugh and I found in Pacifica and detangled without impaling ourselves with the hidden octopus lure.

This hamster-wheel of thought inside my little head — which occasionally seeps out in spurts like this — is why I treasure Zinfandel grapes and Blue Agave, because honestly, I would probably crack from over-analysis and psychic pain if nature hadn’t at least given us grapes and succulents to take the edge off existence from time to time.

I’d like to think non-human animals have an innate equanimity and understanding — or some outlet that provides an occasional escape from their own travails. You’ve probably seen the video that circulated from a French “documentary” where elephants and baboons are stumbling drunk after ingesting alcoholic fruits. I believe this was staged with sedatives, or so I read. Not good ethics, dare I say. The reality of public drunkenness among wild animals is probably closer to what animal physiologist Barry Pinshows says in this Scientific American article: “A drunk bat is a dead bat.” It probably doesn’t pay for animals to lose their hold on reality, the way we occasionally can.

So, because it is most often the case that animals suffer our afflictions and technologies without much reprieve, the upshot of this post is threefold: 1) I’m so grateful for organizations like International Bird Rescue and all other wildlife rescuers and facilities (my own wildlife-rehab mentors included) — all of whom intervene when human intervention is detrimental — and who give me hope in humanity and hope in positive outcomes; 2) For all of my mixed feelings about Facebook and social media, links like the ones from Bird Rescue are the best part of my scrolling through news feeds; and, 3) My involvement with birds and other wildlife always, for better and worse, brings me to a much deeper understanding of the cycles and interconnectedness that make it impossible for me to separate my actions and my consumption from these end results.

As Paul Kelway writes in the Bird Rescue blog:

Accidents happen. We choose reusable materials and diligently pick up after ourselves, but as hard as we each try to shrink our own ecological footprint, most of us have let a plastic bag get away from us in the wind or lost a sandwich wrapper off the side of our beach towel. Or what about the disposable coffee cup you forgot on the roof of your car? Each of us has played a part in the pollution we see around us, and each of us has the power to do something to reduce the damage.

With respect to fishing gear, there is much more awareness and action now than in years prior, an important and proactive development. In fact, here in the Pacific Northwest, there’s a strong ghost net retrieval program in place, gathering up derelict nets and fishing gear which would otherwise entangle many marine species. NOAA’s Marine Debris program is tackling the issue on a larger scale. In the Bird Rescue post above, Kelway links out to information about ocean plastics — a different facet of the same problem: See NRDC’s page on plastics reduction.

If this post seems like it’s missing a point and a central focus, well, that’s because sometimes I have trouble coming up with the point of the things I see, sometimes heartbreaking things — and the tangential connections I make from all of that. Lately, my skills have been comparably under-utilized for the sake wildlife and over-utilized in the necessity of modern survival. And that, I imagine, leads to existential disorganization, maybe despair. Almost always, though, it awakens some sense of imperative about what really matters. And what started this post was precisely that: a picture of a pelican with a fishing lure piercing its pouch … safe in the sanctuary of a place where, as Larry wrote, “every bird matters”. Every bird matters. Every sea lion matters. Every salmon matters. And, in this household, where we’re hosting several thriving house and garden spiders, every spider matters. I have to keep reminding myself of this reality when what I’m doing feels like the tiniest drop in the big bucket of calamity.

For a slightly different take on the theme of small acts of compassion, read Michael Mountain’s post On Picking Up Starfish. (Mountain is one of the founders of Best Friends Animal Sanctuary, an unbelievably wonderful domestic animal rescue in the canyons of Kanab, Utah.)

Ingrid, when I was in Florida it was commonplace to see birds tangled in fishing line or hooked in some manner. It always broke my heart when the bird could still fly because that meant they weren’t sick enough to capture and remove the manmade mess they were caught in.

I wish I had an answer to these problems but I believe that many good people are working on finding solutions.

And yes, every bird and animal matters.

I agree with you, Mia, thank you — about many good people. I can’t believe I’m actually quoting the first George Bush, but remember his 1000 Points of Light? It ties in with the quote at the top of my blog, from Year of Living Dangerously — “Add your light to the sum of light.” I sometimes forget that. I mean, I don’t forget it. I forget how important it is. I get overwhelmed and feel under-committed by virtue of time. The circuitous nature of this post is testament to losing my psychic way at times, needing to find my way back to just being the only point of light I can be: one … among millions.

cant stand finishg cant stand finishg in lakes myself, always forget the mosquito repellent, and i moved to the silver valley in north idaho (only a 30 min drive to montana) about 4 years ago from california and i understand completely why people up here dont like californians, people up here are so mutch nicer, see how many random people wave hi to you in your town if you live in california or a place like it, its easy to adapt up here