Dwindling Salmon Numbers at the Ballard Locks

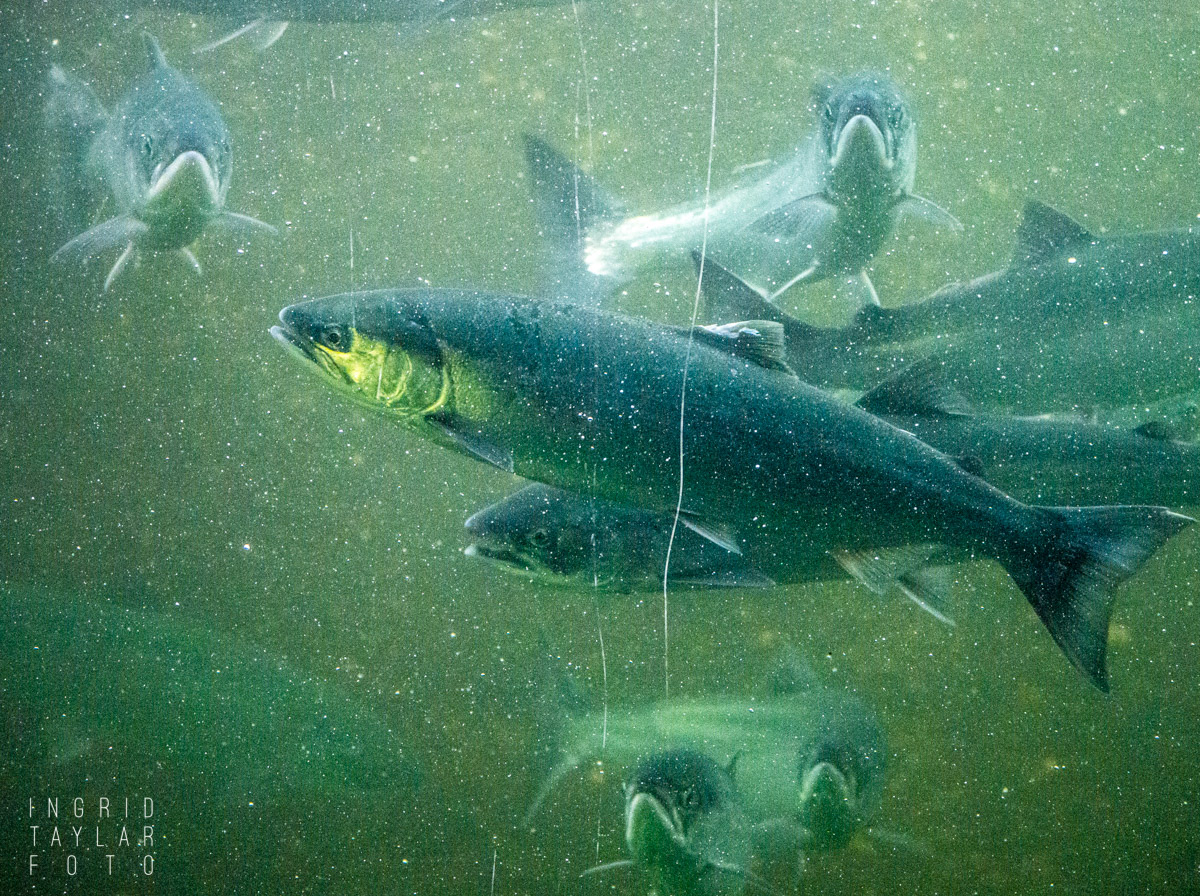

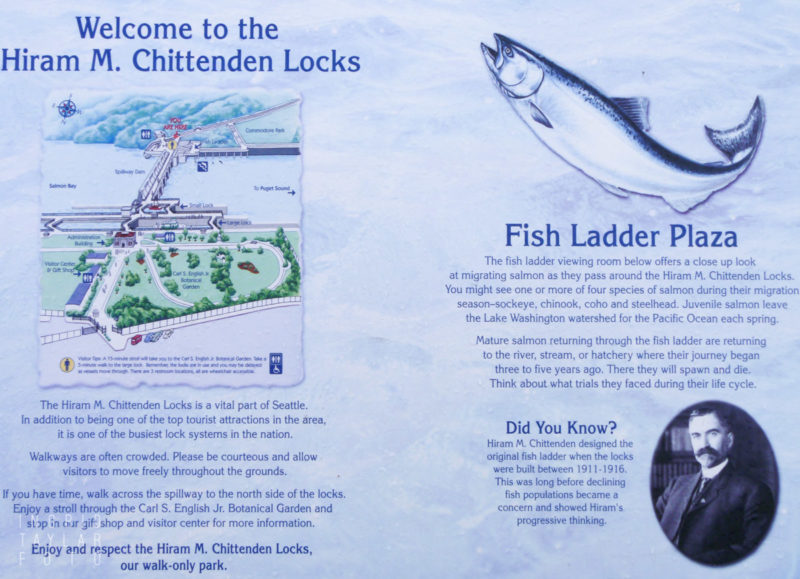

Every year of the five years we lived in Seattle, I watched the salmon come through the Ballard locks, following their own clocks. First the sockeye, leaping and drifting into the viewing windows in June, in numbers higher than 100,000. The hulking Chinook followed, the aqua kings upon whom the resident orcas feast and depend for their very existence. The coho then sidled in, their silver selves peaking in September. And the steelhead, once numerous, now rarely or never seen, we were fortunate to view just a few times. The factors that plague all salmon and their survival are the same issues likely leading to the steelhead’s decline: pollution, dams, over-harvesting, habitat destroyed. This year, 2019, the Ballard Locks are seeing a drastically lowered count, just 17,000 sockeye counted in early August.

The Salmon Cycle

I’ve written about salmon numerous times over the years, and find myself thinking about them now, sitting behind my California desk, missing the turn of autumn soon to come, where my former self would have been perched at the edges of Puget Sound, Lake Washington, and the streams beyond, witnessing the poignant miracle that is their life and their rebirth. It’s a cycle I didn’t understand or fully appreciate until I saw it unfold in the person of each salmonid, in the arduous course of a simple imperative: to swim upstream. And now, with the salmon’s survival at stake in a warming climate replete with dwindling food sources and growing pathogens, that balance of life and rebirth is tenuous. If it goes, so go the orcas and the ecosystem that’s so dependent on salmon, more than 130 species are nurtured by the salmon’s presence.

Despite its critical importance in our world, the salmon cycle is one lost to many of us, my former self included, when the natural rhythms of our world are blocked by the engines of modernity — the noise, the high-intensity LEDs of the night, the cement and metal barriers, the tools of civilization that, paradoxically, cause us to lose the civility of our original nature. As I write this, my soundscape outside the open window is the screech of construction, layering the city with the columns and slabs of new development. My urban cubicle couldn’t seem farther from our true source, a source which is both theirs and mine.

Salmon Nourish the Ecosystem

Knowing the salmon, even from the periphery, reminded me of that simple imperative of existence that all of us share, and the essence, the life force that fuels us all. Absent the social frameworks, the dress, the star ratings, and the metallic finish of city life, we should all be so noble as salmon. They are exemplars in the case study of interconnectivity, living for themselves in the oceanic depths, then later giving life to others, as they lay their last eggs, and lie in the shallows upstream, their mission fulfilled, their completed selves left to nourish the rest. Would that we humans find a way to do the same, to nourish and heal the earth rather than deplete her.

Excerpted from an earlier post, Climbing the [Salmon] Ladder of Success:

Summer means salmon runs at the Ballard Locks fish ladder . . . twenty-one watery steps from Puget Sound, to the ship canal, to the fresh water spawning grounds where the returning salmon were born.

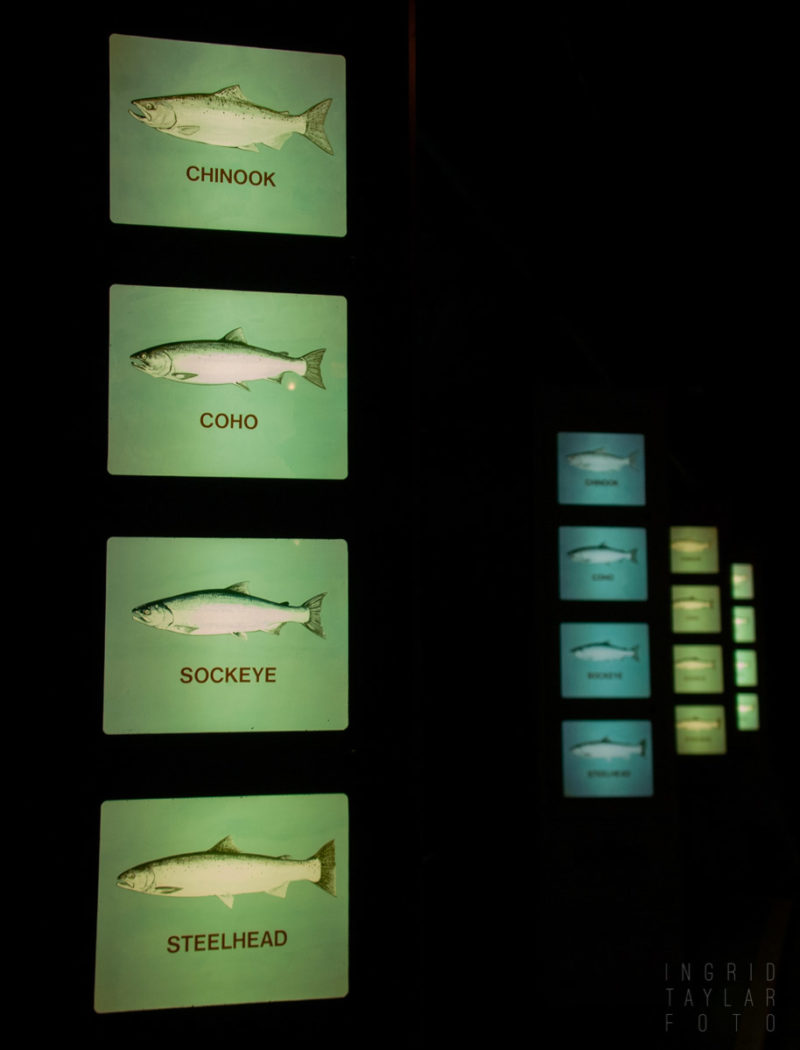

Salmon Displays at the Ballard Locks Seattle

Salmon are a miracle of navigational skills, sometimes migrating thousands of miles during their years in the ocean, possibly guided by magnestism in the same way homing pigeons navigate with help of the earth’s magnetic fields.

Salmon at the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks Fish Ladder

The Salmon Spawning Cycle

The experience that is salmonid is circular, cyclical, and eternal. Were it not for the blockades we humans have erected, the warm and shady estuarine nurseries we’ve scraped away, the rivers and creeks we’ve tapped to trickles, salmon would be leaping upstream by the 20-thousands, as they did in the time of Lewis and Clark. Still, even with each challenge we’ve put before them as species, salmon persist in going home. It could be a most poetic and romantic notion were it not a burning imperative. Salmon insist on hearing the ancient call of their own forebearers — the call for birth and rebirth in the salt-ways, fresh-ways, and pebbled redds of Northwestern streams.

Salmon jumping at the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in Ballard/Seattle:

The Salmon Return Home

Then, salmon ultimately find their way to their birthplace by an imprinted sense of smell: the scent of plants, gravel, the transitional smells of salt water to brackish to fresh, aromas that beckon the Chinook, Coho, Sockeye (and the occasional endangered Steelhead) homeward.

Wild salmon, most threatened or endangered in Washington, squander all of their energy, immunity and body fat to finally dig their redd (nest) and spawn before dying. Hatchery salmon swim a divergent path but live parallel lives, muscling their own way back to their hatching ponds.

Salmon upstream in Issaquah, Washington

Salmon entering the ladder at the Issaquah Hatchery in Washington

Salmon at Issaquah Hatchery